Here is a paragraph.

Born about 1789 in the Rocky Mountains of Idaho, Sacagawea was a Lemhi Shoshone. In the year 1800 she was captured by a raiding party of Hidatsa warrior and brought her back to their nation along the Knife River in what is today central North Dakota. Sacagawea was adopted into the Hidatsa tribe, and later given in marriage to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader who lived among them.

In this painting Sacagawea and her baby "Pomp" have been portrayed as she may have looked in the spring of 1805. Her attire includes some fine examples of ways in which Indian women used natural materials to accent their beauty. She is dressed in an early plains style dress made of two deerskins. The yoke of this dress is painted gold and is outlined with deer fur and accented with a deer’s tail on the front. The dress is an example of everyday working attire of the early style, few of which survive in museum collections. Sacagawea carries a wood and deer’s antler rake, a common tool among Hidatsa women, expert farmers who owned the fields they worked.

The only African American on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, York was also the only member who had no choice about whether or not he would go. As a slave, he was bound to do what he was told by his master, William Clark. It was said that York and William Clark grew up together, and were about the same age which would mean that York was born in Virginia about 1770, and was roughly 34 years old at the time the expedition began. The journals indicate that York was a large man, a little over-weight, and very strong.

On November 23, 1805, when a decision was made about where the Corps would spend the winter, each member was given an equal vote, including York and Sacagawea. This incident may be the first recorded instance in American history of an African American voting.

In the painting, York is shown as a proud hunter during the expedition as recorded in the journal entry of August 24, 1804. On that date Clark described York as carrying a small deer on his back and killing another for the stew pot.

The Moreau river scene shows the men in the morning as three hunters were sent out. The men I’ve chosen for the painting are Drouillard, looking at sign, and the Field brothers with the two horses the Corps had at the time. The Fields are in their issue hunting frocks, round hats and linen trousers with “gaithers”. They also would have been issued their rifles (I believe 1792 contract rifles), hunting bags and horns, and belts with scalping knives. These were all acquired at Harpers Ferry and are included in Lewis’ manifest. The orders for the period required the men to have short hair and be clean shaven. Drouillard was not military, but hired as a hunter so probably wouldn’t have been under the same uniform requirements.

To their rear the men are tending a fire and “branding trees”, a task we know they worked on that morning. My guess is they used Lewis’ brand found in the Columbia river, or something similar. I’ve chosen to show them working on one of the massive Sycamores common in that day. They regularly grew to a size we would find almost impossible to believe today.

The first rays of the sun sparkle on frosted branches as the men of the Corps of Discovery labor to build the "pettyaugers" that will move them and their baggage upriver after the spring thaw. On February 28, 1805.

At this point in the journey much of the men's clothing was probably in it's final stages of wearability. There were a limited quantity of the watch or blanket coats that were issued to the men for guard duty. Camping out and being away from the shelter of the fort, it's likely that this small detachment of men were issued all that were expendable. These coats were made from white, "point" blankets with blue stripes, collars and fold-down cuffs. The "points" were stripes that indicated the quality and size of the blanket.

After working steadily through the end of February and into March the men manhandled the six finished pirogues about a mile and a half to the Missouri River where three were floated down to Ft. Mandan. The other three had to be carried the rest of the way due to ice choking the river. Once there, they were corked, pitched and tarred and prepared for the journey ahead.

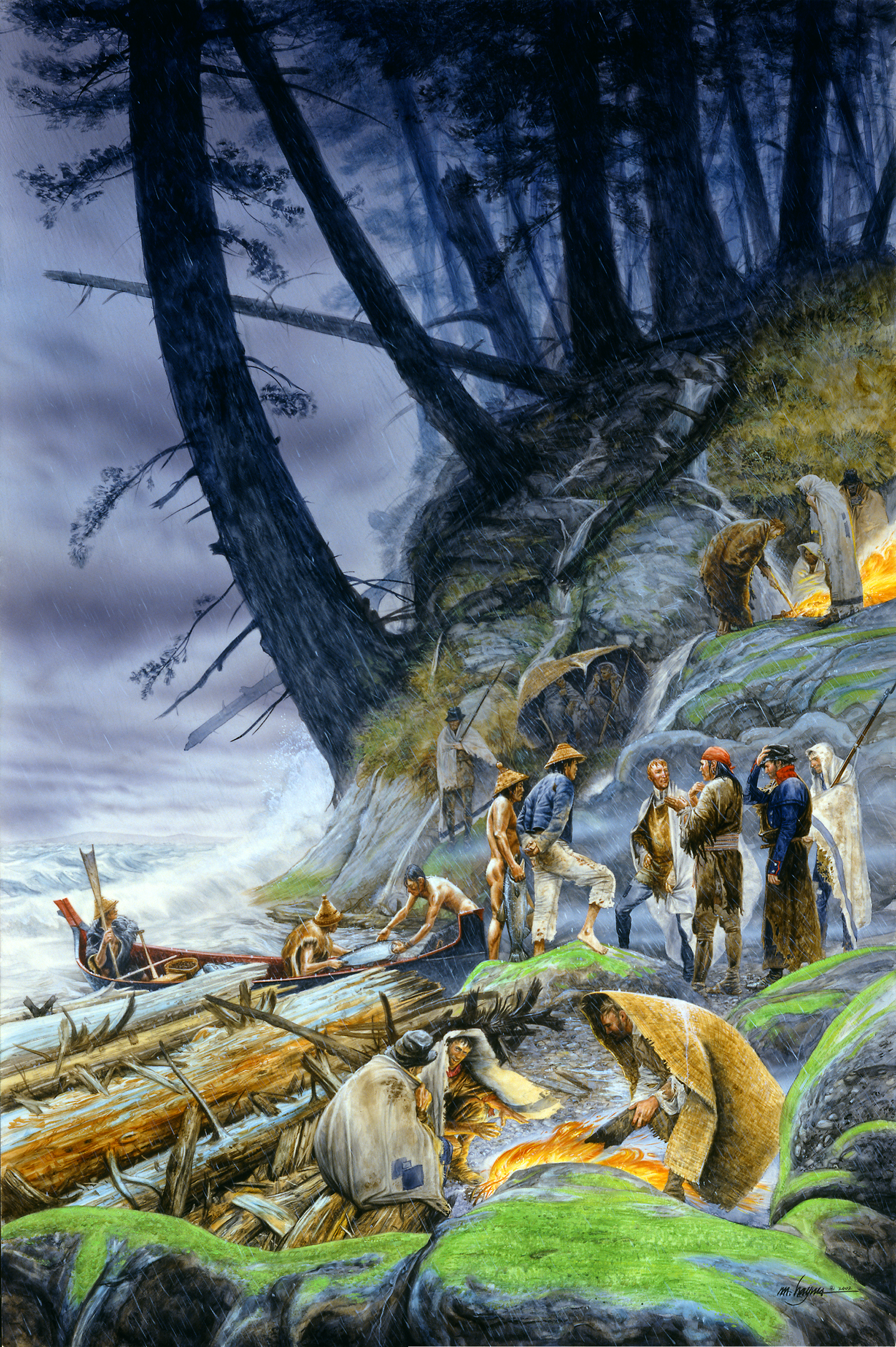

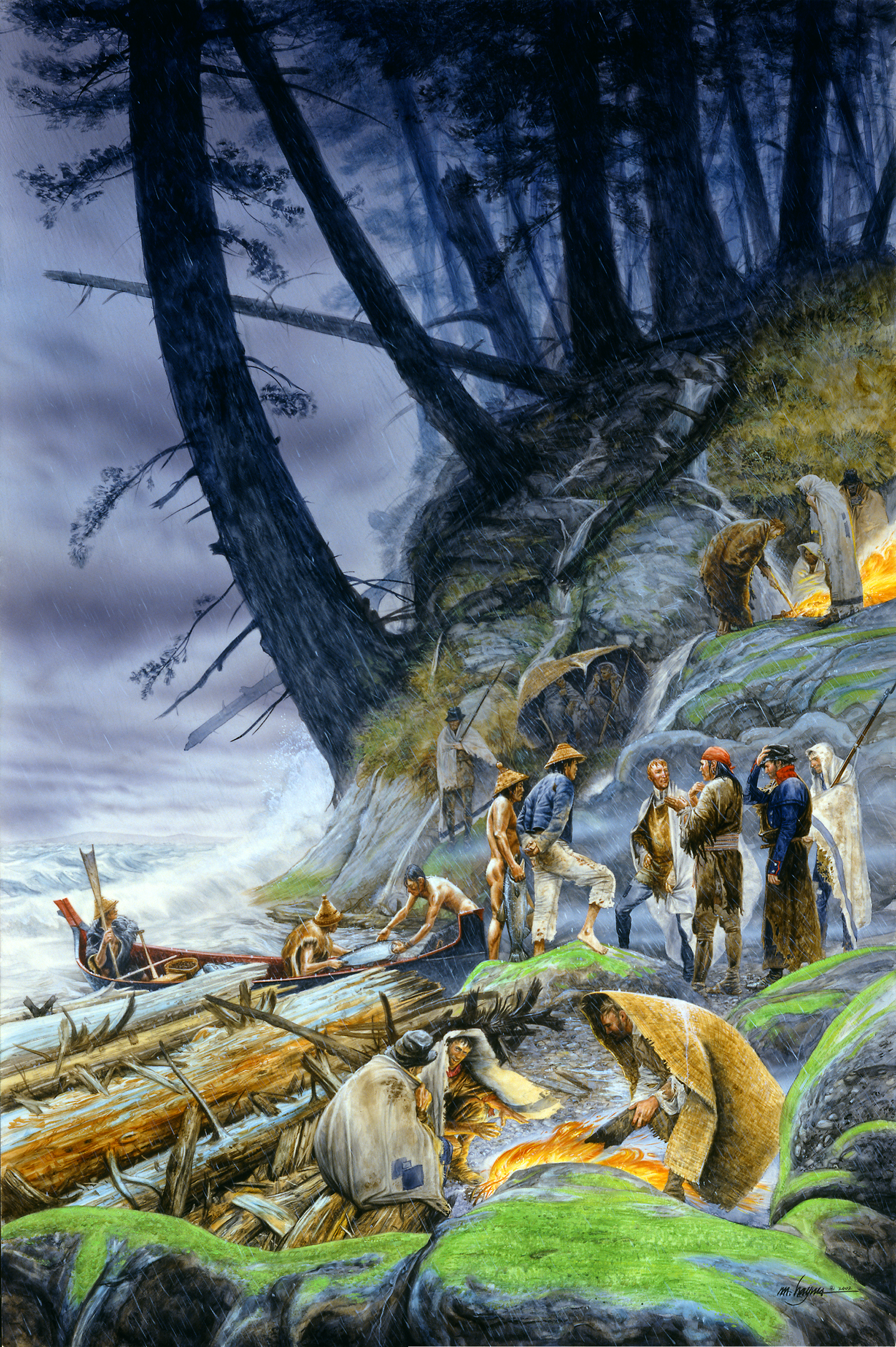

Clark's journal entry of November 11, 1805 described the day as being "truly a disagreeable one". After days of rain and wind the Corps of Discovery was trapped on a wave-beaten stretch of shore just miles from the Pacific Ocean. Soaked to the skin, their leather clothing literally rotting off their backs, the members of the expedition huddled around fires for warmth. Unable to paddle forward or back because of the tremendous surf, they had been forced into a shallow bay ringed by steep, rain sodden hillsides that offered no protection. Stones, dislodged by the torrents of rain water from the hillsides above, fell on the crew. At high tide those that hadn't found shelter in the rocks and crevices were forced to sit and sleep on the massive logs that floated in clusters along the shoreline. Many became sick from the brackish water and the constant undulation of the logs, and there was the very real danger of being crushed between them. The crew had no clothing or supplies other than what they had with them. The food supply had been reduced to pounded fish.

Clark was astonished to see a small canoe with five Indians paddle into the cove through "...tremendious waves brakeing with great violence against the Shores." These Indians were most likely Chinook, and their canoe was loaded with salmon. The Chinook traded 13 salmon for some fish hooks and other "trifling things", giving the men the first fresh food they'd tasted in days.

Stumbling out of their tent after being awakened by the Sergeant of the Guard, William Clark and Meriwether Lewis stand awestruck below shifting curtains of light across the Northern sky. The early morning of November 6, 1804 was not the first time the men of the expedition had seen the aurora borealis but Clark described the scene in his journal entry of that day in much more detail than their earlier sighting.

In this scene Lewis, Clark and the Sergeant of the Guard have stepped away from the lines of tents where they were living while the fort was being constructed to see more clearly above the tree line. Fort Mandan's first line of "huts" had been erected and puncheons were being split from the local cottonwoods to form the ceilings of the men's quarters. Work on raising the second line of huts had just begun the morning of the borealis.

The appearance of the Northern Lights were another sign that the furious pace of construction on the fort had to continue in order to beat the first snows of the fast approaching Northern plains winter.

This full-length portrait of Meriwether Lewis shows the explorer in civilian clothes in Washington, D.C. just prior to his departure for the West. Lewis was known as somewhat of a dandy, and he is depicted wearing the newest fashions of the period. Skin tight white pantaloons contrast with his dark, high waisted, curved front riding coat with clawhammer tails. The most popular color for civilian coats in the United States during the early 19th century was dark blue, referred to in period documents as “the national color,” and complemented with a double row of brass buttons. Fashionable gentlemen wore Hessian boots with their scalloped tops and tassels. The army cockade on the far side of Lewis’ round hat indicates that although he is dressed in civilian attire he is an active-duty military officer.

This is the way I believe Meriwether Lewis may have looked in present day Montana near the Continental Divide. He's wearing his military chapeau and has on an Indian style leather war shirt which has strips quilled in the Mandan fashion on each arm. The expedition sent back to President Jefferson a couple of these war shirts that they collected. He also has on a pair of undecorated, plains style 'mockersons' (Wm. Clark’s spelling). His linen overalls are well patched and stained. He mentioned in his journals that the first time he strapped on his knapsack was in the mountainous region in Montana. It's a military issue, New Invented Knapsack which was painted a brick red. His hunting equipment consists of a leather hunting bag, a powder horn with a carved and blackened spout and the rifle he was painted with in George St. Memin's post-expedition portrait.

Perhaps the most interesting article he's holding is the spyglass. The Lewis family owned this English telescope until the early 1970's and believes it actually accompanied Lewis on the expedition. Its main tube is a beautiful honey colored wood with brass fittings.

On June 4, 1804 William Clark recorded in his journal, “Our mast broke by the boat running under a tree.” His entry didn’t point out who had been to blame and it may easily have remained a mystery as none of the other journal writers did either except one. Sgt. John Ordway was more specific, “Our mast broke by my steering the boat (alone) near the shore,... the mast got fast in a limb of a sycamore tree & broke it very easy.” I feel this ability to assume responsibility may have been reflective of the conscientious manner with which Sgt. Ordway seemed to execute all his duties: faithfully and fully. This incident occurred very close to present day Jefferson City, Missouri and caused a delay as the necessary repairs were made.

Up until this emergency they seem to have been enjoying a rare moment of sailing. Usually the massive keelboat had to be poled or cordelled up the river, a feat we can only marvel at today.

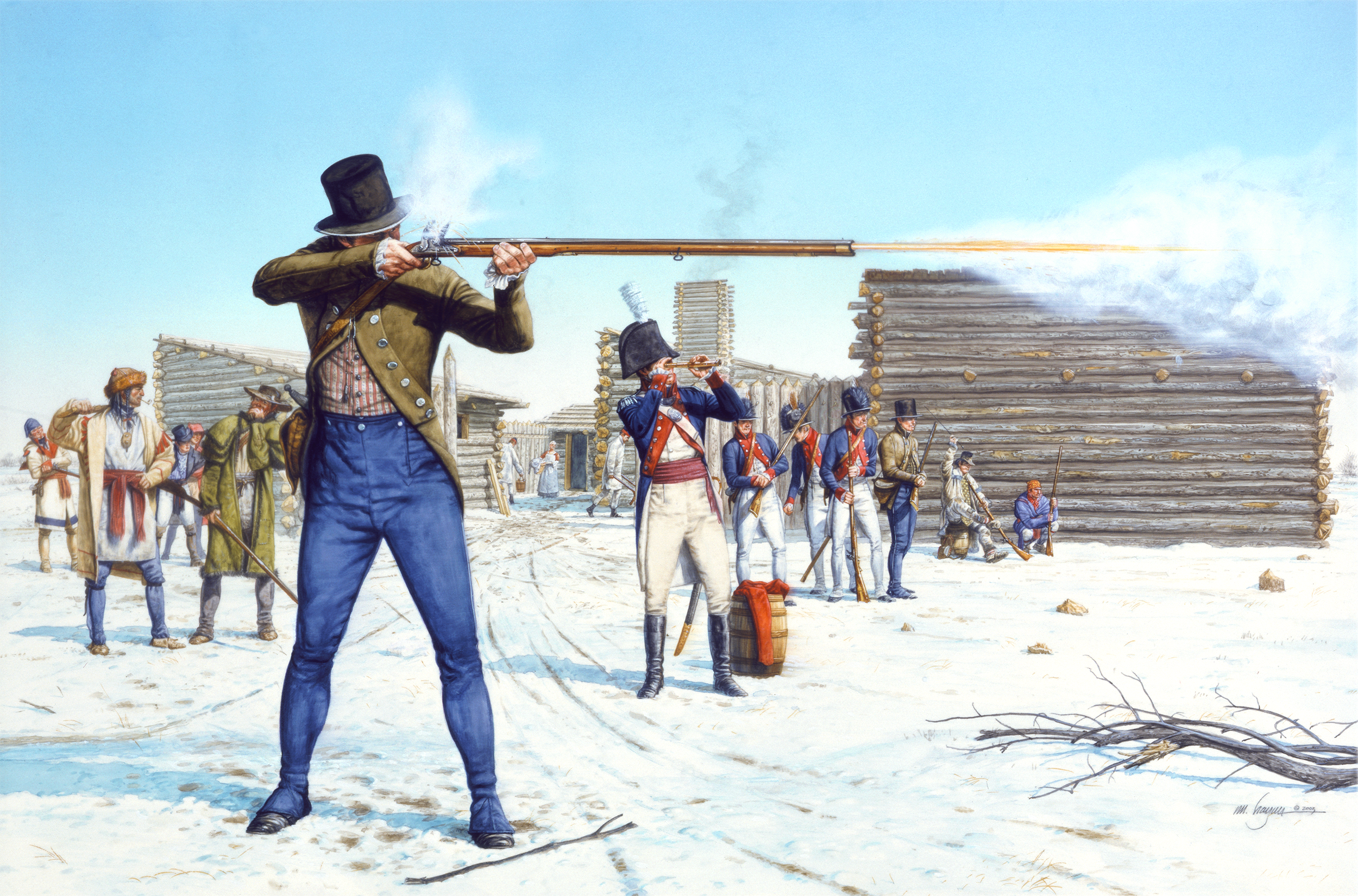

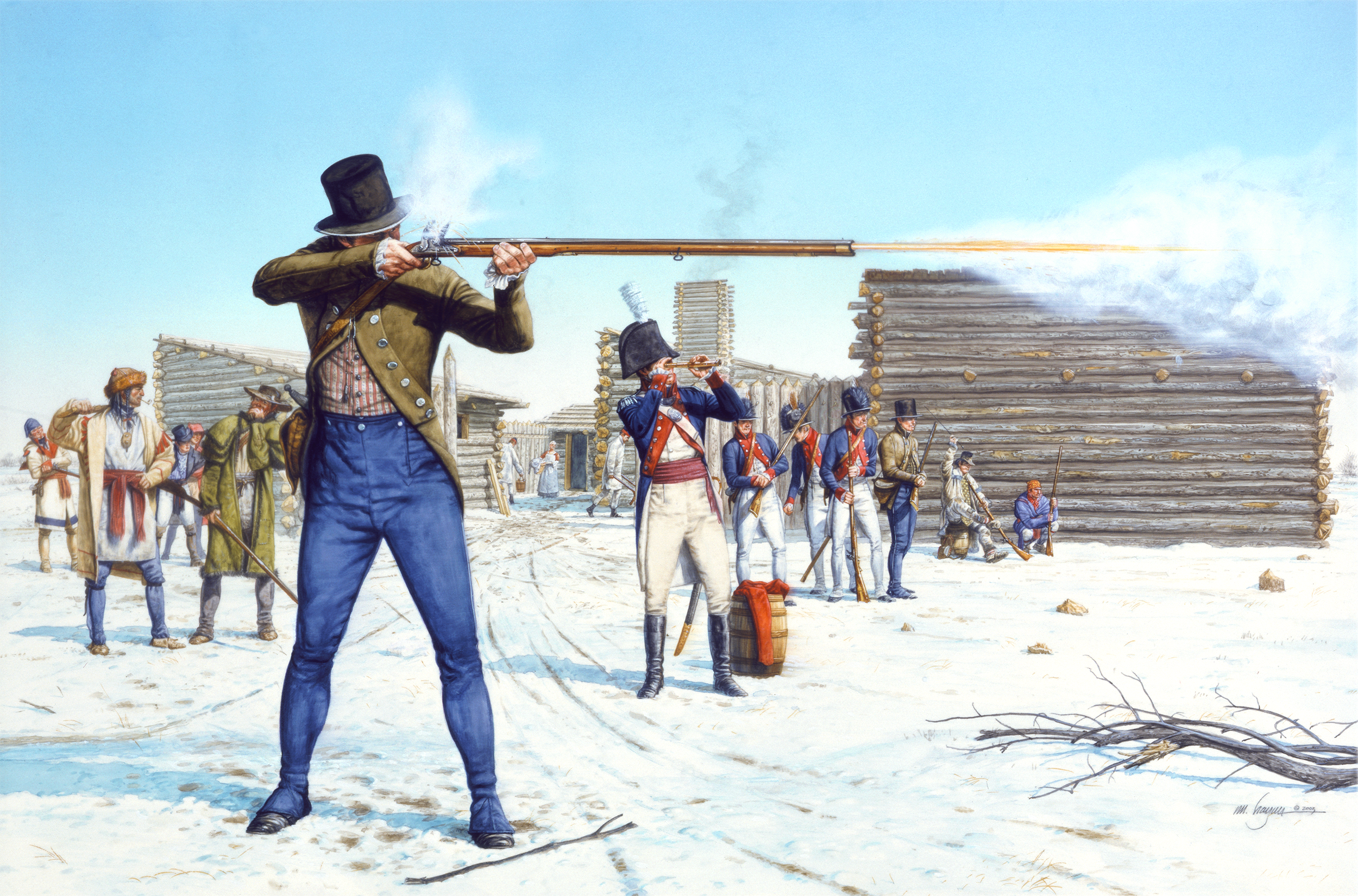

One of the methods William Clark employed to build comradery among the disparate group of soldiers and frontiersmen that had been assembled at Camp River DuBois, was to allow a number of shooting matches between the men of the fort and groups of locals. There were three matches recorded that winter and Clark couldn’t have set up a better scenario. After losing the first match (and a gold coin put up by Clark as the prize) the men of the fort must have been humiliated. They were professional soldiers and woodsmen, handy with firearms and individually selected for their skills to form the Corps of Discovery yet they had lost to a group of country people, possibly farmers and French tradesmen. The men were eager to get their revenge. On January 16th, 1804, the men of the fort challenged the locals to a rematch. John Colter, Rueben Field, Peter Weiser and the rest were set to compete for the two prizes- a pair of leggings and their pride.

Unwilling to suffer another defeat, the men of the Corps are anxious to make every shot count and Rueben Field does. It’s the best shot of the day and brings the leggings, and a renewed sense of pride, back into the fort.

On November 11, 1804 as the men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition worked steadily to complete the construction of Fort Mandan before the coming Northern Plains winter, Toussaint Charbonneau and his two wives, both of the Snake nation, came to call. They came bear- ing gifts of “buffalow Robes”. This was most likely Lewis and Clark’s first encounter with the woman who would play a significant role in the success of the Expedition. Her name was Sacagawea, and she was at the beginning of an adventure that would shape a nation.

One of the greatest hazards that the men of the expedition encountered was the river itself. Constantly shifting currents, underwater snags and huge rafts of trees moving downriver made the bowman’s job one of constant alertness and labor. This scene depicts one of the moments when the keelboat was in danger of capsizing. The boat had hit a hidden sandbar and is tipping dangerously to larboard. The men are frantically attempting to keep her upright. Just as suddenly the sand boiled out from underneath righting the vessel and nearly pitching the men into the murky water.

The 55 foot long keelboat was modified by Clark at Wood River to include storage lockers running the length of the gunwales. They may have had cleats or strips of wood laid on at intervals to give the men purchase while poling.

The rain fell in sheets, wetting Sgt. John Ordway to the skin as he used the brow of a low ridge as a screen, in his quest to hunt bison. Feeling he had gone far enough, he raised up to his full height, only to come face to face with an enormous bison bull. Complicating matters was the fact that he was wearing a bright red shirt. Red was the color which wisdom said was the very worst to wave in front of an animal. The bull looked at him and walked toward him in a menacing way. Ordway raised his rifle and shot at the huge animal's head, grazing it and sending the bull. As Ordway tried to reload, the rain wetted and fouled his gun so badly that he decided to return to camp.

Here is a paragraph.

Born about 1789 in the Rocky Mountains of Idaho, Sacagawea was a Lemhi Shoshone. In the year 1800 she was captured by a raiding party of Hidatsa warrior and brought her back to their nation along the Knife River in what is today central North Dakota. Sacagawea was adopted into the Hidatsa tribe, and later given in marriage to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader who lived among them.

In this painting Sacagawea and her baby "Pomp" have been portrayed as she may have looked in the spring of 1805. Her attire includes some fine examples of ways in which Indian women used natural materials to accent their beauty. She is dressed in an early plains style dress made of two deerskins. The yoke of this dress is painted gold and is outlined with deer fur and accented with a deer’s tail on the front. The dress is an example of everyday working attire of the early style, few of which survive in museum collections. Sacagawea carries a wood and deer’s antler rake, a common tool among Hidatsa women, expert farmers who owned the fields they worked.

The only African American on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, York was also the only member who had no choice about whether or not he would go. As a slave, he was bound to do what he was told by his master, William Clark. It was said that York and William Clark grew up together, and were about the same age which would mean that York was born in Virginia about 1770, and was roughly 34 years old at the time the expedition began. The journals indicate that York was a large man, a little over-weight, and very strong.

On November 23, 1805, when a decision was made about where the Corps would spend the winter, each member was given an equal vote, including York and Sacagawea. This incident may be the first recorded instance in American history of an African American voting.

In the painting, York is shown as a proud hunter during the expedition as recorded in the journal entry of August 24, 1804. On that date Clark described York as carrying a small deer on his back and killing another for the stew pot.

The Moreau river scene shows the men in the morning as three hunters were sent out. The men I’ve chosen for the painting are Drouillard, looking at sign, and the Field brothers with the two horses the Corps had at the time. The Fields are in their issue hunting frocks, round hats and linen trousers with “gaithers”. They also would have been issued their rifles (I believe 1792 contract rifles), hunting bags and horns, and belts with scalping knives. These were all acquired at Harpers Ferry and are included in Lewis’ manifest. The orders for the period required the men to have short hair and be clean shaven. Drouillard was not military, but hired as a hunter so probably wouldn’t have been under the same uniform requirements.

To their rear the men are tending a fire and “branding trees”, a task we know they worked on that morning. My guess is they used Lewis’ brand found in the Columbia river, or something similar. I’ve chosen to show them working on one of the massive Sycamores common in that day. They regularly grew to a size we would find almost impossible to believe today.

The first rays of the sun sparkle on frosted branches as the men of the Corps of Discovery labor to build the "pettyaugers" that will move them and their baggage upriver after the spring thaw. On February 28, 1805.

At this point in the journey much of the men's clothing was probably in it's final stages of wearability. There were a limited quantity of the watch or blanket coats that were issued to the men for guard duty. Camping out and being away from the shelter of the fort, it's likely that this small detachment of men were issued all that were expendable. These coats were made from white, "point" blankets with blue stripes, collars and fold-down cuffs. The "points" were stripes that indicated the quality and size of the blanket.

After working steadily through the end of February and into March the men manhandled the six finished pirogues about a mile and a half to the Missouri River where three were floated down to Ft. Mandan. The other three had to be carried the rest of the way due to ice choking the river. Once there, they were corked, pitched and tarred and prepared for the journey ahead.

Clark's journal entry of November 11, 1805 described the day as being "truly a disagreeable one". After days of rain and wind the Corps of Discovery was trapped on a wave-beaten stretch of shore just miles from the Pacific Ocean. Soaked to the skin, their leather clothing literally rotting off their backs, the members of the expedition huddled around fires for warmth. Unable to paddle forward or back because of the tremendous surf, they had been forced into a shallow bay ringed by steep, rain sodden hillsides that offered no protection. Stones, dislodged by the torrents of rain water from the hillsides above, fell on the crew. At high tide those that hadn't found shelter in the rocks and crevices were forced to sit and sleep on the massive logs that floated in clusters along the shoreline. Many became sick from the brackish water and the constant undulation of the logs, and there was the very real danger of being crushed between them. The crew had no clothing or supplies other than what they had with them. The food supply had been reduced to pounded fish.

Clark was astonished to see a small canoe with five Indians paddle into the cove through "...tremendious waves brakeing with great violence against the Shores." These Indians were most likely Chinook, and their canoe was loaded with salmon. The Chinook traded 13 salmon for some fish hooks and other "trifling things", giving the men the first fresh food they'd tasted in days.

Stumbling out of their tent after being awakened by the Sergeant of the Guard, William Clark and Meriwether Lewis stand awestruck below shifting curtains of light across the Northern sky. The early morning of November 6, 1804 was not the first time the men of the expedition had seen the aurora borealis but Clark described the scene in his journal entry of that day in much more detail than their earlier sighting.

In this scene Lewis, Clark and the Sergeant of the Guard have stepped away from the lines of tents where they were living while the fort was being constructed to see more clearly above the tree line. Fort Mandan's first line of "huts" had been erected and puncheons were being split from the local cottonwoods to form the ceilings of the men's quarters. Work on raising the second line of huts had just begun the morning of the borealis.

The appearance of the Northern Lights were another sign that the furious pace of construction on the fort had to continue in order to beat the first snows of the fast approaching Northern plains winter.

This full-length portrait of Meriwether Lewis shows the explorer in civilian clothes in Washington, D.C. just prior to his departure for the West. Lewis was known as somewhat of a dandy, and he is depicted wearing the newest fashions of the period. Skin tight white pantaloons contrast with his dark, high waisted, curved front riding coat with clawhammer tails. The most popular color for civilian coats in the United States during the early 19th century was dark blue, referred to in period documents as “the national color,” and complemented with a double row of brass buttons. Fashionable gentlemen wore Hessian boots with their scalloped tops and tassels. The army cockade on the far side of Lewis’ round hat indicates that although he is dressed in civilian attire he is an active-duty military officer.

This is the way I believe Meriwether Lewis may have looked in present day Montana near the Continental Divide. He's wearing his military chapeau and has on an Indian style leather war shirt which has strips quilled in the Mandan fashion on each arm. The expedition sent back to President Jefferson a couple of these war shirts that they collected. He also has on a pair of undecorated, plains style 'mockersons' (Wm. Clark’s spelling). His linen overalls are well patched and stained. He mentioned in his journals that the first time he strapped on his knapsack was in the mountainous region in Montana. It's a military issue, New Invented Knapsack which was painted a brick red. His hunting equipment consists of a leather hunting bag, a powder horn with a carved and blackened spout and the rifle he was painted with in George St. Memin's post-expedition portrait.

Perhaps the most interesting article he's holding is the spyglass. The Lewis family owned this English telescope until the early 1970's and believes it actually accompanied Lewis on the expedition. Its main tube is a beautiful honey colored wood with brass fittings.

On June 4, 1804 William Clark recorded in his journal, “Our mast broke by the boat running under a tree.” His entry didn’t point out who had been to blame and it may easily have remained a mystery as none of the other journal writers did either except one. Sgt. John Ordway was more specific, “Our mast broke by my steering the boat (alone) near the shore,... the mast got fast in a limb of a sycamore tree & broke it very easy.” I feel this ability to assume responsibility may have been reflective of the conscientious manner with which Sgt. Ordway seemed to execute all his duties: faithfully and fully. This incident occurred very close to present day Jefferson City, Missouri and caused a delay as the necessary repairs were made.

Up until this emergency they seem to have been enjoying a rare moment of sailing. Usually the massive keelboat had to be poled or cordelled up the river, a feat we can only marvel at today.

One of the methods William Clark employed to build comradery among the disparate group of soldiers and frontiersmen that had been assembled at Camp River DuBois, was to allow a number of shooting matches between the men of the fort and groups of locals. There were three matches recorded that winter and Clark couldn’t have set up a better scenario. After losing the first match (and a gold coin put up by Clark as the prize) the men of the fort must have been humiliated. They were professional soldiers and woodsmen, handy with firearms and individually selected for their skills to form the Corps of Discovery yet they had lost to a group of country people, possibly farmers and French tradesmen. The men were eager to get their revenge. On January 16th, 1804, the men of the fort challenged the locals to a rematch. John Colter, Rueben Field, Peter Weiser and the rest were set to compete for the two prizes- a pair of leggings and their pride.

Unwilling to suffer another defeat, the men of the Corps are anxious to make every shot count and Rueben Field does. It’s the best shot of the day and brings the leggings, and a renewed sense of pride, back into the fort.

On November 11, 1804 as the men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition worked steadily to complete the construction of Fort Mandan before the coming Northern Plains winter, Toussaint Charbonneau and his two wives, both of the Snake nation, came to call. They came bear- ing gifts of “buffalow Robes”. This was most likely Lewis and Clark’s first encounter with the woman who would play a significant role in the success of the Expedition. Her name was Sacagawea, and she was at the beginning of an adventure that would shape a nation.

One of the greatest hazards that the men of the expedition encountered was the river itself. Constantly shifting currents, underwater snags and huge rafts of trees moving downriver made the bowman’s job one of constant alertness and labor. This scene depicts one of the moments when the keelboat was in danger of capsizing. The boat had hit a hidden sandbar and is tipping dangerously to larboard. The men are frantically attempting to keep her upright. Just as suddenly the sand boiled out from underneath righting the vessel and nearly pitching the men into the murky water.

The 55 foot long keelboat was modified by Clark at Wood River to include storage lockers running the length of the gunwales. They may have had cleats or strips of wood laid on at intervals to give the men purchase while poling.

The rain fell in sheets, wetting Sgt. John Ordway to the skin as he used the brow of a low ridge as a screen, in his quest to hunt bison. Feeling he had gone far enough, he raised up to his full height, only to come face to face with an enormous bison bull. Complicating matters was the fact that he was wearing a bright red shirt. Red was the color which wisdom said was the very worst to wave in front of an animal. The bull looked at him and walked toward him in a menacing way. Ordway raised his rifle and shot at the huge animal's head, grazing it and sending the bull. As Ordway tried to reload, the rain wetted and fouled his gun so badly that he decided to return to camp.